Synthesis

Synthesis of Your Own Ideas

Professors want to see evidence of your own thinking in your essays and papers. Even so, it will be your thoughts in reaction to your sources:

- What was the author really trying to say?

- What parts of them do you agree with?

- What parts of them do you disagree with?

- Did they leave anything out?

- What does an author’s work lead you to say?

It’s wise to not only analyze—take apart for study—the sources, but also to try to combine your own ideas with ideas you found in class and in the sources.

Professors frequently expect you to interpret, make inferences, and otherwise synthesize—bring ideas together to make something new or find a new way of looking at something old. (It might help to think of synthesis as the opposite of analysis.)

ACTIVITY: Creative Thinking

Synthesis is a creative act. Are there places, things, activities, or situations that you already use to spark your creativity? Sometimes even simple things can help us be more creative. Take a look at the article 5 Ways to Spark Your Creativity for some tips.

The book Thinker Toys, by Michael Michalko, can help you expand your ability to think creatively. The author’s web page contains fun but challenging thinking exercises, including this one that lets you practice making associations between seemingly disparate concepts.

Getting Better at Synthesis

To get an A on essays and papers in many courses, such as literature and history, what you write in reaction to others’ work should use synthesis to create new meaning or show a deeper understanding of what you learned.

To do so, it helps to look for connections and patterns. One way to synthesize when writing an argument essay, paper, or other project is to look for themes among your sources. So try categorizing ideas by topic rather than by source—making associations across sources.

Synthesis can seem difficult, particularly if you are used to analyzing others’ points but not used to making your own. Like most things, however, it gets easier as you get more experienced at it. So don’t be hard on yourself if it seems difficult at first.

EXAMPLE: Synthesis in an Argument

Imagine that you have to write an argument essay about Woody Allen’s 2011 movie Midnight in Paris. Your topic is “nostalgia,” and the movie is the only source you can use. In the movie, a successful young screenwriter named Gil is visiting Paris with his girlfriend and her parents, who are more politically conservative than he is. Inexplicably, every midnight he time-travels back to the 1920’s Paris, a time period he’s always found fascinating, especially because of the writers and painters—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Picasso—that he’s now on a first-name basis with. Gil is enchanted and always wants to stay. But every morning, he’s back in real time—feeling out of sync with his girlfriend and her parents.

You’ve tried to come up with a narrower topic, but so far nothing seems right. Suddenly, you start paying more attention to the girlfriend’s parents’ dialogue about politics, which amount to such phrases as “we have to go back to…,” “it was a better time,” “Americans used to be able to…” and “the way it used to be.”

And then it clicks with you that the girlfriend’s parents are like Gil—longing for a different time, whether real or imagined. That kind of idea generation is synthesis.

You decide to write your essay to answer the research question: How is the motivation of Gil’s girlfriend’s parents similar to Gil’s? Your thesis becomes “Despite seeming to be not very much alike, Gil and the parents are similarly motivated, and Woody Allen meant Midnight in Paris‘s message about nostalgia to be applied to all of them.”

Of course, you’ll have to try to convince your readers that your thesis is valid and you may or not be successful—but that’s true with all theses. And your professor will be glad to see the synthesis.

There is a lot more you can learn about creating synthesis in scholarly writing. One place synthesis is usually required is in literature reviews for honors’ theses, master’s theses, and Ph.D. dissertations. In all those cases, literature reviews are intended to contribute more than annotated bibliographies do and to be arguments for the research conducted for the theses or dissertations. If you are writing an honors thesis, master’s thesis, or Ph.D. dissertation, you will find more help with Susan Imel’s Writing a Literature Review.

ACTIVITY: Balancing Sources and Synthesis

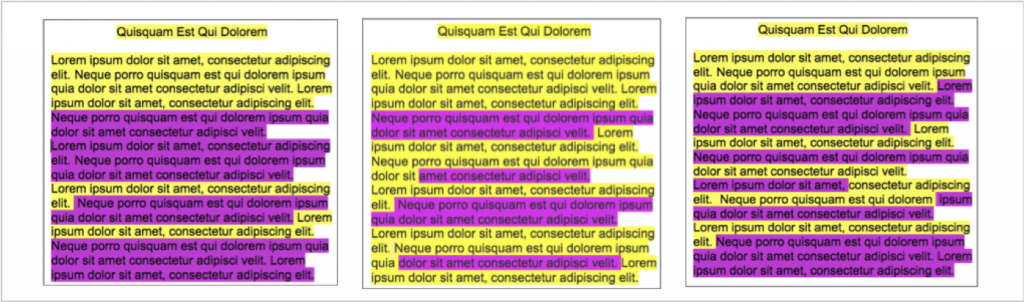

Here’s a technique to quickly assess whether there is enough of your original thought in your essay or paper, as opposed to information from your sources: Highlight what you have included as quotes, paraphrases, and summaries from your sources. Next, highlight in another color what you have written yourself. Then take a look at the pages and decide whether there is enough you in them.

For the mocked-up pages below, assume that the yellow-highlighted lines were written by the writer and the pink-highlighted lines are quotes, paraphrases, and summaries she pulled from her sources. Which page most demonstrates the writer’s own ideas? See the bottom of the page for the answer.

Source: Joy McGregor. “A Visual Approach: Teaching Synthesis,” School Library Monthly, Volume XXVII, Number 8/May-June 2011.

ANSWER TO ACTIVITY: Balancing Sources and Synthesis

The answer to the “Balancing Sources and Synthesis” Activity above is:

The Middle Sample.

The yellow-highlighted sections in The Middle Sample show more contributions from the author than from quotes, paraphrases, and summaries of other sources.

License

Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research by Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.